The “Universal Curl”

or, the bonnet’s impact on multicultural hair care

The Kalogeras sisters. They’ve taken over the digital feed of curl girls worldwide, sharing their routines, techniques, and product promotions. Three brunettes are the centerpiece of millions of curl-hopefuls’ blood, sweat, tears, and wasted money on products that don’t work, just to have hair like the sisters. Now, the trio holds a new title: trailblazers. They proudly wear their protective hair bonnets, flaunting them in recent videos and even (*gasp*) wearing them in public. What these young, white women have done for normalizing bonnet culture cannot be overlooked – at least, in the eyes of their young, also white audience.

HairTok influencers (left to right) Demitra, Sunday, and Eliana Kalogeras.

The truth is that, for hundreds of years, it’s been black people who have pioneered products like the bonnet. They’ve shaped black history through their innovations under a singular, unifying roof of curl maintenance. However, that roof is expanding: other people want in. In the face of expanded accessibility, thanks in part to “HairTok” influencers, communities reckon with this new line between inclusivity and breaking boundaries. Many fear that the powerful history and culture that went into these historically-black techniques and products is now overshadowed by intense consumerism and a cultural takeover by other races.

For most who rally against the bonnet’s new, multicultural popularity, it’s not the accessibility that’s the problem, but rather, the lack of recognition for its significance. It’s a painful, continued reflection of hundreds of years of hair history, where black hair has been controlled, shunned, and regulated by other cultures, only for those cultures to adopt black practices without the credit. Bonnets are an incredible curl maintenance tool that, when shown in such a white-dominated fashion as the Kalogeras sisters’ digital bubble, comes off as a bridge between cultures and the beginnings of the “Universal Curl Girl”, a struggle that transcends race to tangle with tresses instead. But some bridges aren’t meant to be crossed. The “Universal Curl” will never exist through infringing on the delicate and personal black history that comes with the bonnet, but only with a greater respect and understanding for why it can’t exist can the bonnet finally be a feel-good staple in every person’s hair care routine.

The Problem: White People Like to Reinvent the Wheel

It’s not just a HairTok thing–black-pioneered hair care has been a debate dragged into the spotlight for decades. As recently as 2019, when entrepreneur Sarah Lindenberg founded Nitecap, white people have found ways to reinvent the wheel time and again. In Lindenberg’s case, it was taking credit for silk bonnets. Her business skyrocketed from her claims that she had invented the bonnet (under a different, patented name, of course), and the controversy over her taking credit paid off in the short term.

Sarah Lindenburg (left), founder of NiteCap, photographed by Katherine Holland for Fashion Magazine, 2019.

Allure Magazine, c. 2015.

Lindenberg later apologized after massive backlash, but the coverage she got failed to properly explain why an apology was needed–even in Fashion Magazine’s story, the strong correlation with black history was nothing more than a one-line edit, buried in the middle of a paragraph to slip past readers’ eyes. So why was this important detail so crucially overlooked? Was it a journalistic oversight, or a deliberate choice to draw focus away from the racial implications of Nitecap’s foundation?

In my eyes, these tiny omissions pile onto a mountain of hypocrisy. From taking credit for others’ achievements to forcing black hairstyles onto white heads (no, Allure, forcing an afro on straight hair isn’t 2015 “chic”), the lack of respect and knowledge about black hair feeds a vicious cycle.

Fashion tutorials on how white people can have “black hairstyles” like the afro show just how out of the loop so many are, when black people are relentlessly criticized for the very nature of the afros the magazines try to emulate! It’s both incredibly unserious and unacceptable that articles like the one in Allure Magazine exist, when, in 2010, an Alabama woman had her job offer revoked for refusing to cut off her dreadlocks, and over 1 in 5 young black women have been sent home from work because of their hair. It’s more than just unprofessionalism. There has never been a fashion accessory, a piece of oneself so central to styling, that has been as closely tied to one’s identity and personhood as hair. When such behavior is enabled, it becomes about that person’s livelihood as well.

But when hair is commercialized, as seen with the rapid growth of HairTok, the feed becomes more than just spreading helpful tips. The second TikTok shop launched commissioned products, with bonnets and hair oils at the forefront of its list, that personhood, that story of the bonnet, became lost to its audience. Creators with little-to-no hair expertise have hopped on the bandwagon to promote and get paid. This includes loads of non-black people trying to make money while talking about a product they don’t fully understand. The TikTok algorithm has begun to push low-effort content like this into people’s feeds (in the case of my feed, it’s Chinese livestreams selling factory-made bonnets), and paid sponsorships and advertisements have become harder to distinguish.

Does this mean the Kalogeras sisters are doing wrong by showing themselves wearing bonnets and using hair oils? It’s not a problem to normalize multicultural haircare, not in the slightest. But with no education and, frankly, no tangible reason why that education is needed, it allows younger generations to grow up unaware of the products they use daily, and to naturally associate them with people like the Kalogeras sisters instead of their original creators.

When you wear a bonnet, you wear years of hard-earned history–both pain and triumph, shame and pride, woven into silk on your head. So, let’s start by giving credit where credit is due. People, as much as some try, can’t reinvent the wheel when they don’t share the culture it belongs to. All it takes is promoting and uplifting voices in black hair care and making sure the context is more than just a one-line edit.

The History: Built From the Ground Up

“Don't touch my hair / When it's the feelings I wear / Don't touch my soul / When it's the rhythm I know / They don't understand / What it means to me / Where we chose to go / Where we've been to know”

Don’t Touch My Hair by Solange

When we examine the centuries of literal blood, sweat, and tears put into black hair care, it’s easy to see why many are so hesitant to hand over their practices. After all, black hair is a huge subject of pride, yet it carries painful memories for many.

The journey to the modern bonnet begins with some of those most painful memories. Especially on American plantations, slaves’ heads were forcibly shaved in an act of conformity and humiliation. Slaves who came from Africa during the Transatlantic Slave Trade often carried rich and vibrant cultures with them. African head wraps were not only protective accessories, but designators of status. The way one wore these wraps, from Namibian to Yoruba culture alike, showed wealth and ethnicity. But when they were enslaved on plantations, these traditional head wraps, especially in the case of women, were used as symbols of “inferiority” in the eyes of their owners. Their identities and livelihood were stripped from them, and their own points of cultural pride were weaponized into symbols of white ownership.

Over time, as the wounds of slavery slowly healed, people began to grow out and regain agency over their hair. This expression marked a turning point of joy for many generations, who finally felt the freedom to take care of their hair as they wanted. And with unique textures known as the 4A-4C range, black hair needed extra care and protection.

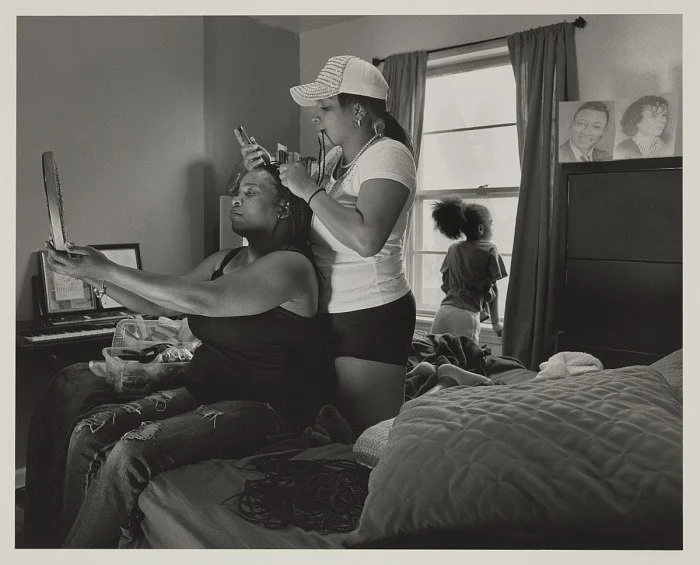

Shea Doing Crochet Braids in Her Cousin Andrea’s Hair for Andrea’s Daughter’s Wedding, 2016–17. Photograph by LaToya Ruby Frazier.

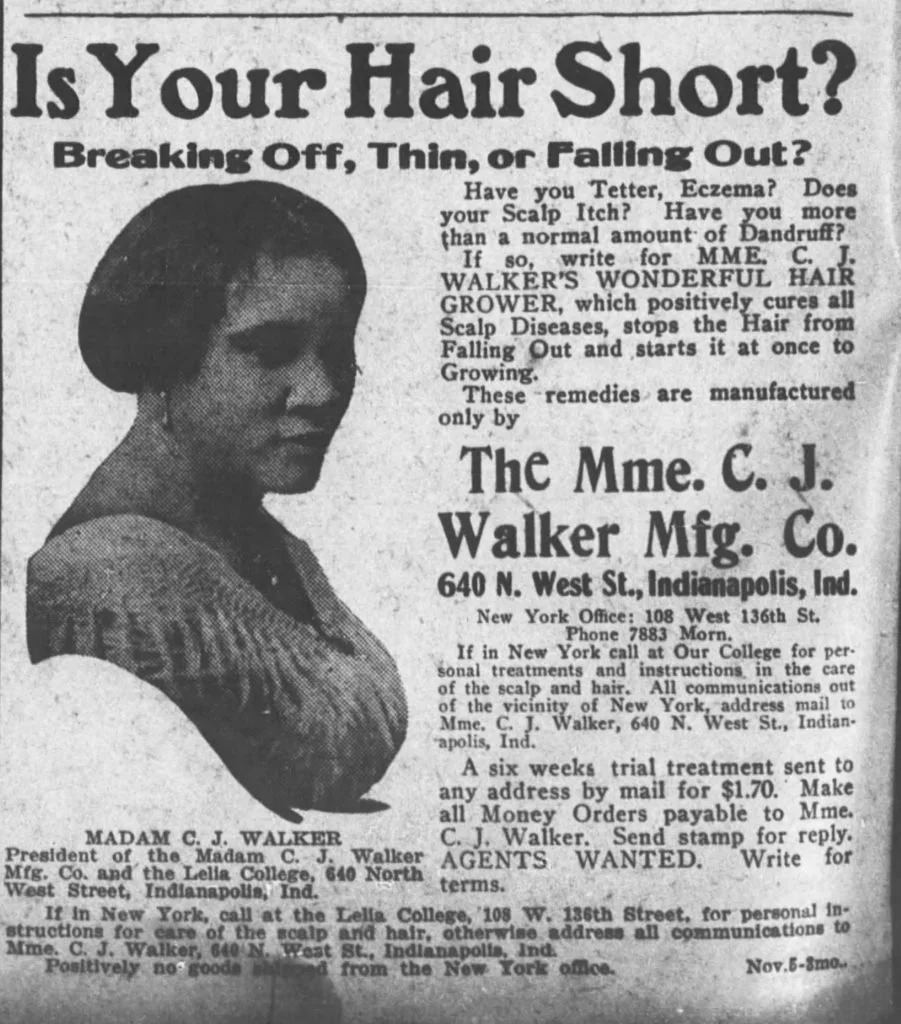

The ‘Madame C.J. Walker’, America’s first black female millionaire who pioneered the art of scalp care.

The modern durag and bonnet, though the dates aren’t exact, came onto the scene around the same time, in the late 50s and 60s. They were initially used to protect chemically processed hair as early as the Great Depression.

In fact, the early 1900s were a renaissance for black voices in hair. Madame C.J. Walker became the first black female millionaire in America after her own scalp troubles inspired her to build an empire. She patented the “Walker system” of products that were tailored to customers’ scalp health and longevity. People began to view black products as innovations in the hair industry. And even now, over a hundred years later, scalp rinses and scrubs pack the aisles at Target, stable (albeit consumerist) reminders of the Walker empire.

This renaissance carried head wraps into the pop culture scene. Women were seen wearing their bonnets outside, while durags, a tighter head wrap more associated with male hairstyles and maintaining wave compression, became a staple of 70s hip-hop. Wraps were everywhere; symbols of progress and pride during the Civil Rights Movement, and so prominent on the rap scene…especially when white artists like Eminem adopted them.

Eminem accepting a Grammy in a durag, 2003.

Nowadays, bonnets come in every shape, size, and color. They’re readily available for hair of any length, and can be bought from a mass-producer business or handcrafted on Etsy for an extra price. The same material that lines the bonnets, often satin or mulberry silk, is now on pillows, sheets, and even giant duvets. With such a growing popularity and online presence, it’s easier than ever to protect one’s hair, thanks to years of black innovations.

It was quite a long road to not only take back black hair care from its painful start in American history, and the bonnet/durag both stand as crowning achievements. The bonnet’s versatility has made it more adaptable for other hair types, sparking interest and controversy alike. And with such a painful history of hiding one’s hair, can the bonnet really be universal? How can its utility today be reconciled with its history? And most of all…is there really such a thing as just hair?

The Universal Curl Girl

One thing’s clear–this reconciliation can’t happen through HairTok alone. In a ten-second video, promoting bonnets and sharing hair care history feels trivializing, no matter the intent. But there’s a divide to be healed, not just across cultures, but within communities, in order to address this ideal of the “universal curl”.

The first problem is that not all black people agree on other cultures adopting bonnets and head wraps. There’s still so much struggle they face with this issue. Every hair product and style under the sun that’s ever been associated with black history has somehow been criticized, so it’s natural for many black people not to embrace it right away–history sadly isn’t just the triumphs of invention and culture, but the negative stigmas and responses too.

Wearing bonnets in public, something the Kalogeras sisters have become famous for doing, is an incredibly divisive issue. Famous black voices have even spoken out against wearing protective styles outside (see a viral Instagram video from celebrity Mo’nique, who refers to these styles as undignified and a bad reputation), but do the Kalogeras sisters get the same backlash? Videos of them wearing bonnets in public get hundreds of thousands of likes, with one of the most liked comments even calling one of them “the queen of bonnets”.

I believe there should be no shame in anyone wearing a bonnet outside–it’s about protecting your hair, after all–but then again, it’s easy for me to say when white people aren’t the ones being criticized. Especially when the criticism comes from years of racism, and black people being held to higher standards of looking professional or even “acceptable”. It’s a deep wound in the hair care world, one that normalizing bonnets in public can smooth over but never fully heal.

The second problem, one I know a lot of curly-haired people have with bonnets, is this feeling of discomfort or even guilt. It sounds unusual at first, but, especially when trying to manage curls for the first time, many non-black people feel uninformed and therefore unsure of themselves. This in itself is a result of increased awareness about these cultural boundaries (which is good) and a lack of education about black hair history (which is unfortunately all too common).

Feeling guilty isn’t a bad thing when it comes to bonnets. It’s natural, and merely reflects this unfortunate, eggshell atmosphere that years of cultural discomfort have cultivated. Being unafraid to feel afraid and ask for permission marks a desire to be more self-aware in a society that often looks past these things. I firmly believe that if there were more history and credit woven into the consumerism chain, fewer people would have such a queasy conscience about taking care of their curls. Some good starting boundaries are not taking credit for what isn’t your own (à la Nitecap) and supporting black hair stylists and creators.

The third, and most damning problem that causes this gap, is that the Universal Curl simply does not exist. Of course, bonnets can’t be “banned” from use; they will always be a tool for curls of all types, and the benefits of preventing breakage and maintaining style can’t be denied. But black and white curls are just so different, not only in texture and maintenance, but in the history that created them. Bonnets and black hair care will forever be used by the masses, and this popularization is good for supporting black businesses. By falling victim to the “consumerism chain” mentioned earlier, there exists an illusion of the universal curl.

Just because we love and care for our hair in similar ways does not make our hair the same; hair holds memories, so goes the famous saying, and it’s rung true for centuries. But even though our curls never tell the same story doesn’t mean that we can’t tell new stories about the universal struggle–just trying to get our hair to stay through the night, and learning to love the style that has shaped millions.