The Twee Revival: Talkin’ Bout a Gentle Revolution

“Where there is strife, there is Twee.”

Amelié dir. by Jeanne-Pierre Jeunet

In 2021, I spent the final year of an unremarkable high school career siloed in my childhood bedroom. Somewhere in the midst of hours-long scroll sessions and poring over Sylvia Plath, I arrived at the ill-fated idea to make a zine. I say “idea,” when really it was a need, a primal urge, a result of my tendency towards idée fixes and manifesto-making. I worked diligently from my bedroom floor to the musical score of my local college radio station, KSPC 88.7 FM. And through this manic daze, with the radio blaring from sunup to sundown, I was introduced to the pantheon of Twee musicians— Heavenly, the Pastels, Talulah Gosh, Camera Obscura, Belle and Sebastian, and the Smiths. The disc jockeys called their sound “twee,” so that's what I decided to call my zine: Twee.

While making Twee, I did not know — nor did I care — about the historical and cultural implications of the word, the eyebrows it might raise, the groans it might provoke; I only knew of it as an adjective that encapsulated me entirely. Sentimental, dopey, earnest, and painfully sincere. I was slower than my peers at everything, slower to romance, slower to maturity, slower to life. I was not in possession of any particular talent or grace that might have earned me some degree of confidence from my classmates or my teachers, yet there I was, quietly creating from the comfort of my room. And I was not alone.

By 2022, #twee was a TikTok trend that had amassed over 85 million views, with creators donning false cat-eye glasses, tartan pencil skirts, knee-high socks, ballet flats, and Peter Pan collars. Twee was gently massaged back into the fashion world, with Coach’s 2022 Spring collection starring Bonnie Cashin-inspired houndstooth and plaid anoraks, A-Line silhouettes, and oversized mini dresses. Every fashion brand from Gucci to Prada to Hot Topic to Free People dashed to turn out a pair of graphic tights. Some critics — those who vividly remembered the age of Twee — bemoaned the shift, conjuring visions of oblivious, kombucha-drinking trust-fund babies raising rents wherever they tread. Yet in 2026, Twee is poised for a fully-fledged revival, not as a punchline about granola-munching Hipsters or ukelele-wielding manic pixie dream girls, but perhaps as the champion for a post-algorithm world.

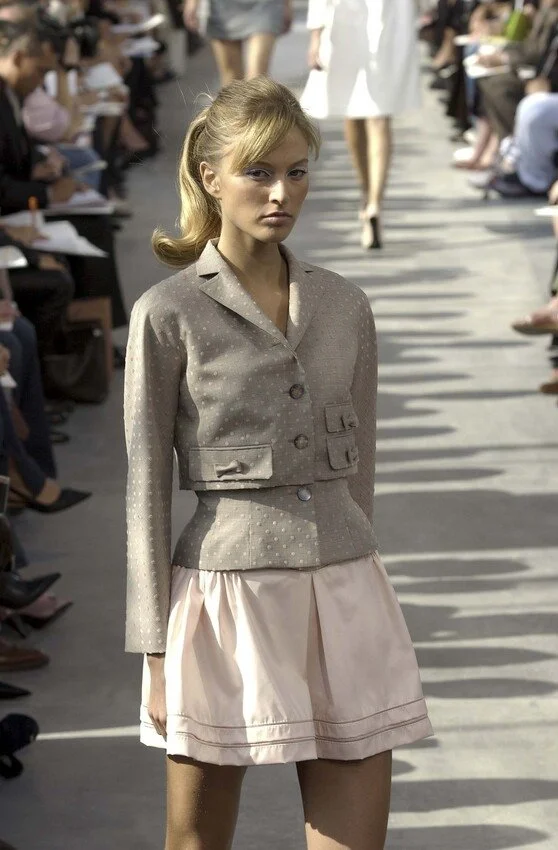

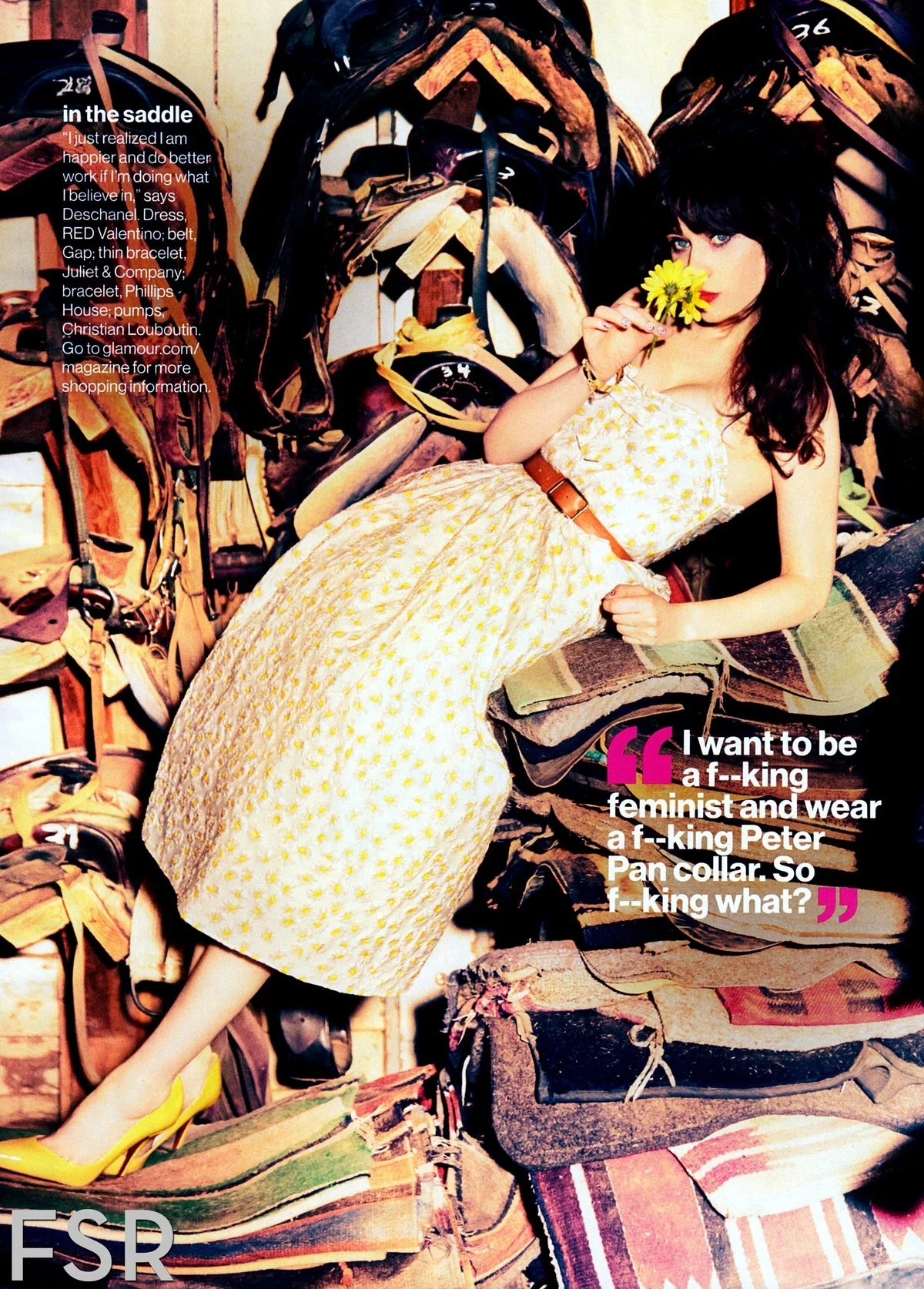

Visually, the Twee Revival is typified by modish fashion prints (polka dots, awning stripes, checks, houndstooth, etc.) and silhouettes, rounded-toe ballet flats and Mary Janes, peacoats, mini skirts, Peter Pan collars and pussy bows, and rosette appliques. “Cozy” motifs such as apples, buttons, ladybugs, and retro, pin-back ribbons that resemble something of a participation award— the prize for a wallflower. Some retailers who sniff out microtrends to capitalize on like bloodhounds have latched onto the Twee Revival and churned out polka dot and apple-printed garments for mass consumption. Yet, what characterizes Twee and what empowers the Twee Revival is an affinity for the outdated, for the slow-moving, for the anodyne. As established by cultural critic and co-host of the Nymphet Alumni podcast, Alexi Alario, the style beats of Twee Revival (which she termed “Whimsymod”) come from the late 1990’s and early 2000’s diffusion lines of larger fashion houses such as RED Valentino (“RED” is an acronym for Romantic Eccentric Dress), Miu Miu (of Prada), and Blugirl (of Blumarine) aimed at a younger audience with a lower price point. And of course, the personal style of Twee icons in the mid- to late 2000’s, Zooey Deschanel and the Fanning sisters. Twee is a practice in retrospective, amounting in renewed interest in figures such as Sylvia Plath, musicians like Kitty Craft and Margo Guryan, the scrappy, scribbly character design in illustrated children’s books such as Charlie and Lola, Eloise, Madeline, Max and Ruby, and Peanuts comics. Along with a cultish reverence for Twee filmmakers, Wes Anderson, Sofia Coppola, and Greta Gerwig.

As with most microtrends, the Twee Revival involves a melange of nostalgia and romance, but unlike most microtrends, the canon is intrinsic to the Twee lifestyle, which was a practically monastic devotion to acquiring and attending to knowledge. In his 2014 book, Twee: The Gentle Revolution in Music, Books, Television, Fashion, and Film, Marc Spitz dutifully graphs the trajectory of Twee, compiling a comprehensive corpus on the histories, literature, music, and films that inspire what he calls the “Twee Tribe.” In the words of Spitz, “You have to read … a lot … and, generally, alone. [...] Simply taking yourself outside of society isn’t enough. Once outside, you have to actually study.” To this end, I would add that the Twee Revival is less a microtrend and more an anti-trend, an acknowledgement and a censure of the whirlwind trend cycle that wrought it. Twee Revival is a softer, less direct, and, critically, a more mature expression of girlhood that is distinctly separate from the cottagecore and coquette aesthetics and from the flamboyantly hedonistic aesthetics of indie sleaze.

For all its posturing and pretension, in the 2000s, being Twee meant a commitment to precociousness, kindness, cultural curation, and intellectual curiosity. Twee necessitated grit and guts. Most of those engaging with the Twee Revival beyond its aesthetic mystique are too young to remember the pitfalls of Twee—the gentrification, the fatphobia, the infantilization. They remember when the aspirational adults, obsessed with mustaches and bespectacled kittens, were voracious learners, teaching themselves to pickle and leatherwork and speak Mandarin. In the 2000s, Twee prized the fruits of slow learning, slow living, and a pre-monetized, pre-algorithmic Internet, the very same tenets that a sector of Gen-Z is fighting to restore. Therefore, it’s not a coincidence that the Twee Revival comes on the heels of people turning in their Instagram and X (formerly known as Twitter) accounts for Substacks, personal curriculums, and blockchain Internet forums like the Nina Protocol and Perfectly Imperfect.

The etymological root of the word “twee” purportedly comes from the way an English toddler might pronounce the word “sweet.” Most dictionary definitions define it as “chiefly derogatory.” Through the ages, “twee” has been leveled as a pejorative towards those who feel too much, an admonishment of naïvete and immaturity. Yet, in the girlhood-obsessed 2020s into which Twee has reemerged, it is now the adult in the room.

If 2023 was the “Year of Girlhood” — as narrowly defined by the ascendance of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, Sabrina Carpenter’s meteoric rise, Lana Del Rey’s Did You know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd?, and confounding fixations on “girl dinner” and “girl math,” baby pink, bows, and friendship bracelets — then 2026 may be the year of the Twee Revival. The coquette, cottagecore, office siren, whimsigoth, and indie sleaze aesthetics have all lent a limb to the Frankenstein's monster that is the Twee of the 2020's, yet I believe what truly animates the Twee Revival has less to do with the resurgence of its natural aesthetic counterparts, and everything to do with the current sociopolitical condition. Twee's peak popularity in the States arrived at the apogee of the 2008 financial crisis, when the economic future of a generation was not just grim but gruesome. As we endure similarly unstable times, the revival of Twee represents what it did back when it was most popular — neither a fully-fledged embrace of the current political climate or an outright denial of it, but a gentle revolution against it. Where there is strife, there is Twee.

The Twee-badours

Photographed by Siena Spagnoli.

In the twilight years of the Punk scene—abounding with internal schisms, rapid commercialization, and the political reigns of Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and the neoliberal class—there was a vacuum within which new modes of subculture could emerge. Throughout the 1970s, Punks were an obstinate vanguard, dictating what could and could not be countercultural with profuse enmity. Punks rejected the “classic,” the sentimental, and the beautiful, positing that such designations had allowed for inequality, totalitarianism, and kitsch to fester. What’s more, Punks were not afraid to excommunicate their own in accordance with these values. When Jonathan Richman—proto-Punk, proto-Twee frontman for the Modern Lovers—crossed the pond to play venues brimming with pierced and pugnacious Punk youths, he was met by a chorus of boos and torrential debris. On their first European tour, the Modern Lovers did not play music reminiscent of “Roadrunner” but instead played soft, mellow dance songs in pressed button-down shirts with tidy, straight-leg trousers. In the end, Punk was destined to collapse at one point or another, perhaps because it could not withstand the weight of its own moral convictions, but it would leave an indelible impact. If the 1960s counterculture was all revolution and the 1970s counterculture was all rebellion, then 1980s Twee culture was a commitment to both—albeit with far less volatility.

The early Twee Tribe was undoubtedly influenced by the bellicose bravado of Punk, yet they, like many, could not cut it as Punks. They could not pull off spiked hair and studded jeans. They preferred the gentler moments of Modern Lovers and the Velvet Underground to their forays into the noisy and the avant-garde. They still listened to the Byrds and the Kinks and all the other 1960s Mods that Punk had long since renounced. In appearance and disposition, they were commensurate to a John Hughes protagonist, not a Johnny Rotten devotee. Punks created what they could without the auspices of institutional support, technical skill, or even talent. And so did Twees.

Postcard Records — a Glasgow independent label originally founded and operated out of Alan Horne’s bedroom — signed Orange Juice and Josef K in the late 1970s. Though the label itself was short-lived, Postcard bands were foundational to Twee and indie pop as a whole. Not least because of their cheery, jangly sound, downstream of Motown, Mod rock, and Punk, but for their fashion sense. The members of Orange Juice were known to sport childlike camp clothes: mismatching patterns, Davy Crockett caps, Boy Scout shorts, and plastic sandals. All the while Josef K, reflecting a heavier modish influence, donned secondhand Oxfam suits and skinny neck ties like kids dressed by their parents for the school dance. Other bands would follow, and by the early 1980s, what had begun in Alan Horne’s bedroom was a full-fledged scene. In his seminal essay, “Twee as Fuck,” Nitsuh Abebe wrote on the genesis of this youth culture, stating frankly, “For their musical cues, they looked to the quaintest, least-cool roots of youth-culture music: girl-groups, 1960s guitar jangle, bubblegum chirp, rainy-day balladry.” I’d add that they dug into closets of childhood memories and expired promises of young adulthood for their fashion identity as well.

Dolly Mixture. Image courtesy of Cherry Red.

The baby-faced members of Dolly Mixture, an all-girl trio, took their name after a sugar-coated pastel confection and bonded over their love for the Shangri-La’s. They wore striped hosiery and pinafores, polka dot charity shop dresses, and trimmed their hair into boyish pixie cuts. The godfather of Twee acts, the Pastels, charmed the Glaswegian Postcard scene and the burgeoning indie scene alike with their Byrdsy, lo-fi jangle. The Pastels, in their anoraks and their cardigans, became a touchstone among the young and the absolute, and an oft-forgotten favorite of Sonic Youth, Kurt Cobain, and the Jesus and Mary Chain, to name a few. On the stateside, there was Beat Happening, a quintessentially Twee trio, formed on a college campus in Olympia, Washington and became the first among equals in the city’s burgeoning indie scene. In 1986, NME released their C86 cassette, which included selections of the 22 “most exciting” independent acts of the time, among them Beat Happening and the Pastels. C86 only further cemented what had been percolating for nearly a decade.

In his book, Spitz maintains the position that underlying Twee was a Punk spirit. This argument can be applied in broad strokes to practically every indie movement. What Twee did is what Punk did: react to stimuli. The same anxieties that drove Punk to an incendiary impulse drove Twee toward an escapist one. The same confluence of neoliberal capitalism and conservative policies that Punk sought to burn down, Twee proposed to rip up and start again. That is not to say that every Twee was a solipsist or a centrist, but that they merely contended with the times on their own terms.

Many of the youths who would go on to be Twee’s most influential figures were beneficiaries of Britain’s Arts Council theater and music programs which suffered significant cuts under Thatcher. Take Clare Grogan, whose breakout role in the 1981 film Greggory’s Girl and leadership of the post-punk band, Altered Images, gained her mainstream recognition. With her polka dot blouses and her Dr. Martens, Grogan was named a “Talulah Gosh” by NME, in reference to Jodie Foster’s childhood role as a doe-eyed showgirl in the farcical gangster film, Bugsy Malone. Yet before her successes, Grogan acted in the Scottish Youth Theatre and was a registered member of the British performing arts trade union. Matt Haynes and Clare Wadd, the co-founders of Sarah Records — under which a range of indie pop and Twee acts such as the Field Mice, Tallulah Gosh, Another Sunny Day, and Blue Boy were signed — were avowed feminists, anti-fascists, and socialists. Haynes and Wadd set out to create a label that was more than a sum of its parts, but that had an objective and an accord. Sarah Records frequently took out ads in music magazines denouncing capitalism, Thatcherism, and the commercial exploitation of pop music. The sleeve notes of the label’s first compilation LP read, “It's just POLITICS, not as some distant unreal end, but as something encaptured in everyday life … no sanctimonious ‘socialist’ pose hawked pop starry-eyed with a Thatcherist gleam when it comes to THE SELL, but something that’s basic and pure…” Sarah notoriously refused to sell 12” vinyl records which they regarded as overpriced consumerist catnip, favoring the much more affordable 7” vinyl. In a piece published in Tribune, Haynes remarked, “This was the era of Margaret Thatcher—the Miners’ Strike, Falklands War, Brixton Riots, all these were recent history. How could you not be political?” Punks in spirit, yet pop lovers at heart, Sarah knew that pop was political, and held their artists to the same standard.

Reclaiming the insult leveled at Grogan with pride, Talulah Gosh would form from a fateful encounter between Amelia Fletcher and Elizabeth Price, who found one another wearing the same Pastels badges to an Oxford club. Another Sunny Day, the solo indie pop project of Harvey Williams, boasted wry, Punkish cynicism over sunny, guitar-driven musical compositions. Williams opens “You Should All Be Murdered,” with the shocking, yet infectiously peppy, “One day when the world is set to right / I’m going to murder all the people I don’t like,” and goes on to identify the targets of this ire as, “The people who are cruel to those who don’t deserve”. The American counterpart to Sarah Records was K Records, an independent record label founded by Beat Happening frontman, Calvin Johnson. Alongside handling the U.S. distribution of many Sarah bands such as Talulah Gosh, K and Sarah had a similar philosophy in that they rejected both Punk’s all-consuming nihilism and machismo as well as the encroachment of music industry corporatization. K housed a diverse roster of artists, from the radically feminist Riotgrrrl act, Bikini Kill, to the musical interlopers, Beck and Modest Mouse, to the purely Twee band, Tiger Trap.

Kurt Cobain was an avowed Shonen Knife fan, and invited the trio to tour with Nirvana in 1991, just as Nevermind was on track to become one of the biggest albums of the decade and of rock n’ roll history. Image courtesy of PR.

By the 1990s, Twee had breached containment, spinning off into various iterations within indie scenes in Sweden, with the Cardigans, in New Zealand, with Tall Dwarfs, and in Japan, with Shonen Knife and the shibuya-kei genre. Amid the ascension of Britpop Twee became only more countercultural. Twee bands such as the Sundays and Heavenly (which emerged under Sarah Records in 1989, formed from the ashes of Talulah Gosh) amended the male-dominated Britpop age with a feminine perspective on both class and gender politics. On the Heavenly single, “Hearts and Crosses,” Fletcher sings over a merry, jangly melody about the guilt and shame a young woman feels after she is sexually assaulted. While collecting unemployment benefits, the Sundays lead vocalist, Harriet Wheeler, and guitarist, David Gavurin, penned what would become the band’s debut single, “Can’t Be Sure,” a delectable earworm with lyrics bemoaning the expectations of propriety in English culture. “England my country, the home of the free / Such miserable weather,” Wheeler trills before adding sardonically, “England’s as happy as England can be / Why cry?” It wasn’t an explicitly political song, not to the extent of “Common People” or even “Parklife” but it was a song that encapsulated the apparent futility of young adulthood, the conflicting pressures of civility and desire with earnest felicity.

After three near-perfect albums, Wheeler and Gavurin withdrew from public life entirely. Following the release of their 1990 debut, Reading, Writing and Arithmetic, Wheeler told Melody Maker magazine, “The songs aren’t about being a rock star, which we aren’t, or being a lovestruck teenager, which we aren’t. They’re just little bits of what feels true.” A Twee generally understood that the title of “rockstar” was a heavy investment with diminishing returns, but so too was the title of “adult.” At its core, Twee was a negotiation with time; with the arbitrary nature of adulthood, the rudeness of responsibility, the aching reminders of childhood ignorance, and the encroaching arrival of political doom. To be Twee was to stay a little while longer in the liminal space between innocence and experience.

Talkin’ Bout a Gentle Revolution: Twee in Post-9/11 New York

Gwyneth Paltrow and Anjelica Huston as Margot and Etheline Tenebaum in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenebaums.

Anachronism and appropriation were perhaps the two most fundamental tenets of Twee, and if they were mere purchases of the movement that emerged in the 20th century, then they would be outright pillars by the 21st. Come 2003, the national temperament had largely and diametrically shifted, and Twee had once again reacted to that stimulus. Beyond the pervasive paranoia and the patriotism of the years following September 11, there was also an ache for escapism. For some, that was an escape into the American ideal: country music and tire swings and star-spangled banners all the way down. For others, it was vicarious voyeurism through a television screen: Paris Hilton’s and Nicole Richie’s extravagant lives, Tyra Banks crowning America’s Next Top Model, Donald Trump firing someone new. For Twee, the escape was not at the end of a tailgate party hoedown nor a reality television marathon, but in a defiant rejection of pop culture. They turned their backs on the new cultivation of “adulthood” entirely—the one seemingly predicated on spite and war hawking and an anxious attachment to the TV. The Twee of this time was, if nothing else, an assault on modernity. (A “gentle” one, of course.)

This rebuke manifested in the practice of obsessive, voracious curation. They filled their personal libraries with titles from Maurice Sendak, Judy Blume, Roald Dahl, Miranda July, and J.D. Salinger, alongside the children’s poetry of T.S. Eliot and William Blake. They nurtured hobbies, crafts, leisurely activities that typically cost very little in the way of money, but much in the way of hours spent alone and indisposed. They turned off the radio and turned to the record shops, amassing record collections that could last several lifetimes. Exchanging patriotism for a more atomized identity, ancestry sequencing also rose in popularity. As Alexi Alario put it, personal genealogy platforms such as 23andMe—which launched in 2007—offered a scientific form of escapism. By identifying with your heritage over your nationality, you could withdraw from being American altogether. Twees created a mythology around themselves, an intractable belief that being the nerds, the virgins, the dorks, and the misfits of the world was not just a good thing, but a moral thing—perhaps, the only moral thing. As the collective opinion on the Iraq War began to sour, Twee grew not only in popularity but in visibility.

Sofia Coppola and Wes Anderson were creating some of their most beloved works such as Marie Antoinette and Lost in Translation, and The Royal Tenebaums and Fantastic Mr. Fox. Mumblecore was ascendant, the two most popular adherents, Noah Baumbach producing and Greta Gerwig directing the delightfully Twee Frances Ha in 2012. Adorkable romances were part and parcel to Twee. Films like 500 Days of Summer, Juno, Amelié, and The Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind pepper their soundtracks with Twee favorites, from the proto-Twee touchstones, such as the Velvet Underground, to younger, newer Twee artists such as the Moldy Peaches. Lauren Child, inspired by Roald Dahl, and the rambunctious girlhoods of Pippi Longstock and Anne of Green Gables, wrote and illustrated a children’s book series that would later become an animated show, Charlie and Lola. In 2007 Yo Gabba Gabba aired on Nick Jr., the passion project of former Punks, Scott Schulz and Christian Jacobs, who wanted to create a children’s show that blended preschool life lessons with indie music for parents to enjoy. Alongside pleas to eat your veggies and learn your ABC’s were offerings from various Twee artists such as Apples in the Stereo, the Shins, of Montreal, and Belle and Sebastian. Twee had not only made the mainstream, it finally broke into the world of high fashion through the aforementioned diffusion lines of Prada, Blumarine, and Valentino, but in the overall shifting sensibilities of established and emerging fashion designers as well.

Louis Vuitton RTW Spring Summer 2003.

Under Marc Jacobs, Louis Vuitton embraced polka dots, swinging skirts, frills, bows, and an overall modish optimism for their Spring Summer 2003 collection. Designers Markus Lupfur, Ryan Lo and Meadham Kirkhoff made outrageously girly lines with brightly-colored feather boas, kitten ear headpieces, and Peter Pan collars; many of them cited Twee as a core inspiration. Founded by Eric and Susan Gregg Koger in 2002, ModCloth was one of the earliest online clothing retailers and became the garment of choice for Twees everywhere, with their most popular items being the quirky swing dresses patterned with owls, cats, and cupcakes. Kate Spade, whose designer handbags had been sported on red carpets since the late 1990s, enjoyed a second wind in the early 2000s. Kate Spade was Twee through and through, not only for her stylish predilection for stripes, polka dots, and quirky statement pieces, but for her sophisticated sense of culture. For the Wall Street Journal, Rory Satran wrote that Spade would host readings of John Knowles and W. Somerset Maugham novels, play Phoenix and Bjork over the loudspeaker of her design atelier, and gift each new employee with her own edition of an etiquette guide that included cheeky little maxims such as, “Admire the polka dots on a Wonder Bread package!”

Spitz names the “cultivation of a passion project,” as one of the most fundamental aspects of Twee. This was true in 1979 when Alan Horne started a record label from his bedroom, but it was even more true in the early 2000’s as the Internet began to mature. Not only did you not need institutional support, talent, or skill to be creative, you didn’t need to go outside at all. This all coincided with a rather oxymoronic romance in the analog and the antiquated: typewriters, record players, penny-farthings, film cameras, jukeboxes, and yellowed, vintage maps. Anything that was made outdated or useless by the arrival of the 21st century was welcome. Online artisanal marketplaces such as Etsy allowed for a new generation of bedroom dwellers to buy and sell their vintage or handcrafted kitschy oddities, putting their lonely hours spent learning a skill to good use. This all culminated in the Twee pledge to “buy local” — to attend your local thrift shop, coffee shop, and farmers market. It was all rather fanciful — and well, twee — as by and large, most of the Twee Tribe was not local to whatever hip city they decided to populate. They tended to bend their cities — be they Los Angeles, Austin, Portland, or London — to their liking, introducing yoga studios and juice bars. Nowhere else was this metamorphosis more apparent than in the Twee capital, Brooklyn, New York City.

Emily Mills photographed by Siena Spagnoli.

In the wake of the September 11 attacks, many people were reluctant to move to New York, thus opening the doors and lowering the costs for the young and wide-eyed Twee Tribe. Brooklyn, the home of Biggie Smalls and Jay-Z, had a traditional demographic makeup of BIPOC, immigrant, and working-class New Yorkers. The Twee economy was a closed circuit. By early 2011, the city’s population had surpassed pre-September 11 levels. Brooklyn had seen the largest share growth. In the early 2010s, Belle and Sebastian and Yo La Tengo were headlining Brooklyn cultural events such as the Celebrate Brooklyn! Festival and the Brooklyn flea became a major tourist destination for Twees everywhere.

This was not the Twee of Sarah Records, who took out ads denouncing capitalism; this was a Twee made by and for well-meaning, yet altogether suffusive entrepreneurs. Although many Twee artisans argued that the price of their products fairly accounted for and compensated the labor that went into them, it should come as no surprise that it was not the traditional working class they were selling such items to. A typical kitten-printed ModCloth dress ran anywhere from $100 to $200. A jar of pickles sold at the Brooklyn flea was upwards of $14. (To put this in perspective in our times of hyperinflation, pickles were generally about $3, even after the 2008 financial crash).

The disparity was through no fault of Twee, of course. The counterculture that would have provided political scaffolding and expedience to Twee had been steadily eroded through cultural conservatism, manufactured consent, and targeted legislation for decades prior. For example, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 reduced regulation within media and allowed for bloated corporations to purchase an unlimited number of media assets in various sectors. This would result in the shuttering of college and independent radio stations, many of which uplifted Black, queer, and female artists. The war on terror allowed for the creation of ambient government surveillance, and everything deemed unpatriotic was sharply monitored, if not outright censored. “It’s a blanket fact that after September 11, nonconformist women were taken off the radio,” Shirley Manson said in an interview with Tanya Pearson for Pearson’s book, Pretend We’re Dead.

Zooey Deschanel for Glamour (July 2013).

In 2020, Anna K. Schnaffer wrote about the political reticence of Twee, saying, “Twee, then, is a symptom of profound cultural exhaustion, a pop-cultural response to the death of grand narratives and radical politics: too weary to fight the corporate capitalist machine, the twee instead create hyper-stylized alternative worlds in which kittens play, ukuleles sound and childhood is eternal. Their basic disposition is melancholy rather than angry, and they will always opt for owl-print wallpaper over kicking against the pricks.”

Nevertheless, Twee had inherited the counterculture. Still more genuine than the corporatized, candy-colored angst of Avril Lavigne and the All-American Rejects, Twees became the new Punks, whether they wanted to be or not. Yet their strongest inclinations were to wallow in their bedrooms and blow raspberries at the meanies. Naturally, it bred resentment. Although Twee was perhaps the most visible it had ever been by the mid-2010s, it was also the culture’s punching bag. SNL made a recurring sketch of Zooey Deschanel’s “quirky kitchen.” FOX News aired segments on the Millennials who spend more on coffee than on retirement plans. The Simpsons aired an episode about the Hipsters whose garden compost caught fire and nearly burned down Springfield. Twee was over, and its Obama-era optimism was gone with it. Yet the awkward and gentle people of the world never fully vanish; they only retreat to the bedrooms from whence they came, so it's fitting that they should remerge to take up the mantle of Twee once more.

Gen-Twee and Visions of an Analog Future

Photographed by An Pham.

Many aspects of Twee—particularly those that could be easily capitalized on—were absorbed into mainstream culture. It’s fashionable to go thrift shopping, to do yoga, to eat health foods, to own a record player, to have an identity hinged on a corpus of tastes and aesthetics. Bedroom dwelling is no longer a cute and quirky night in; it is a pervasive social condition. Gen-Z don’t go to their bedrooms to learn, they go there to rot.

Twee still resonates today, because it pierces through the despair and the cynicism. Twee was obsessed with sincerity and authenticity; they preferred bands that played poorly, yet from the heart. In 2026, the Twee Revival is much more solemn and world-weary than its forebear. Gen-Z is a far more jaded, cynical generation than Millennials, kept pacified by way of irony and TikTok. As the new underdogs, Gen-Z does not seek redemption in society, but rather self-determination.

Bedroom pop, a subgenre of indie pop that emerged in the mid- to late 2010s, carries the sincere, DIY ethos of Twee. Many bedroom artists started off singing sincere and unguarded songs about crushes and unrequited loves. Clairo and beabadoobee made cheeky metaphors about young love out of bubble gum and coffee. Other bedroom pop artists like Frankie Cosmos and Sidney Gish leaned further into Twee, embracing jangly melodies and imperfect vocals, while still writing songs about tender moments. Yet, most bedroom pop artists did what Twee-llineals refused to: they grew up. With her jazzy 2024 album, Charm, Clairo embraced polish and restraint without abandoning the emotional directness that made her music resonate in the first place. Her styling by Nancy Kote and Harper Slate incorporated fun, flirty frills, polka dots, pastels, quirky accessories like pin-back ribbons on stage and on the red carpet, reflecting her maturity with her sustained authenticity.

Clairo performing for the Charm tour in Valentino. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

For Millennials, Twee was an escape: a rebuke of adulthood, a soft landing in times of precarity. For Gen-Z, Twee is not an escape at all, but a reclamation: of time, of tactility, of authorship in a world increasingly flattened by algorithms. Twee cannot guarantee that we will be young forever, but it insists that sincerity survives into the future.

Photographed by An Pham.