The Uniform Effect

A uniform is the world’s fastest sentence. Before you speak, it speaks for you. Brass buttons at dawn. Navy pleats in a school corridor. Scrubs sliding through fluorescent light, redolent of antiseptic and burnt coffee. The same impulse, replete in different fabrics: to consecrate the body and to grant it a station in social orders.

We live in an age that worships individuality as a kind of civic religion, yet we still find ourselves retreating to templates. Sometimes from devotion, sometimes out of fatigue, sometimes out of the desire to be understood without narration. Uniforms are social architecture, a shared vocabulary that travels across rooms and borders. I have always been fascinated by the way uniformity can feel like sanctuary and suppression in the same breath of fabric, relief and restraint, belonging and erasure. This essay traces that paradox through psychology, culture, and fashion, asking what uniforms grant us, what they cost us, and why we keep choosing them anyway.

The Social Architecture of Uniforms

Uniforms are a ubiquitous language, making the abstract corporeal by stitching rules, ranks, and belonging into something the body can wear. In precarious rooms, they promise order; in crowded institutions, they reduce the tedium of deciding how to be read.

In this way, uniforms function as a social wayfinding. They reduce friction in crowded systems by making roles instantly legible. In hospitals, airports, schools, courts, and corporations, uniforms spare us the labor of negotiation. We know who to ask, whom to obey, and whom to wait for. The architecture of the institution is mirrored in the body, turning fabric into a map that tells us how to move without speaking. Modern institutions simply industrialized the same logic for nothing in style is born in isolation.

Note: These images are not intended as historically exact representations. They are contemporary visual interpretations produced through FAST at UCLA, whose editorial and creative efforts made this shoot possible.

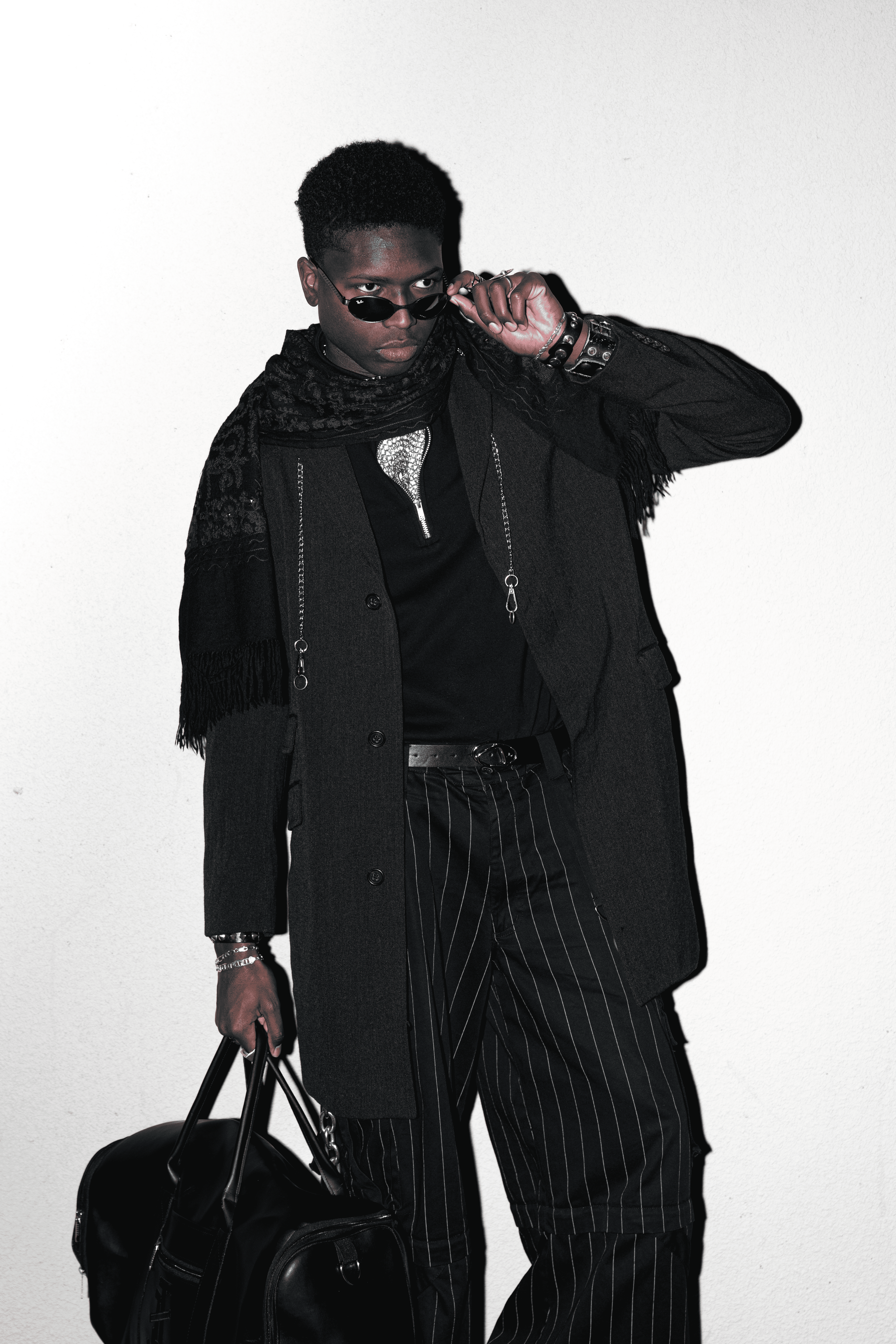

Around the world, art is borrowed, conversations are exchanged, and everywhere symbols travel, carried by trade routes, migrations, marriages, and the quiet imitation of what we admire. And yet, in these repetitions, individuality starts to leak through the seams as a prerogative to deviation: a rolled sleeve rolled over a blazer, a school skirt worn shorter than intended, a bold red lip, a refusal to tuck in; these are small ruptures that let the self breathe inside the standard.

These deviations are not rebellion so much as inhabitation. They create tension within a boundary strong enough to hold but porous enough to be lived inside. This is why the uniform endures, not because we lack imagination, but because we reach for structure when the world feels too wide, and we reach for symbols when language feels inadequate.

The Psychology of the Uniformed Mind

Photography by Cho Giseok.

The mind is a savant of shortcuts, for our brain loves fast categories. Not because it is lazy, but because it is finite, and the world is teeming with variables. It streamlines first impressions to collapse ambiguity and turns a stranger into something the psyche can universally detect. Uniforms do this with particular prowess because they arrive already saturated with implication. You can read a crowd through outfits alone: New York’s coat-and-boot black telegraphs competence, all clean lines and brisk intention; London tailoring is disciplined to the bone, wool and trench and sharp shoulders that hold their line; Mumbai wedding opulence arrives in zari and crystal, brocade flaring under chandelier light, jewelry stacked like lineage. And then the informal uniforms: boardroom restraint, tonal athleisure in butter neutrals and quiet compression, downtown streetwear in oversized silhouettes, and Y2K revivalism.

What you wear does not merely change how you are seen; it changes how you think. This mechanism is known as enclothed cognition, where the mind begins to perform what the garment implies. For example, a lab coat can sharpen attention, not because cotton is magical, but because the mind has learned to associate that silhouette with carefulness, competence, and precision. Conformity is the quieter cousin of obedience. Deviating from the group can trigger a tiny internal alarm that something is misaligned, and the brain, hungry for coherence, nudges you back toward the norm.

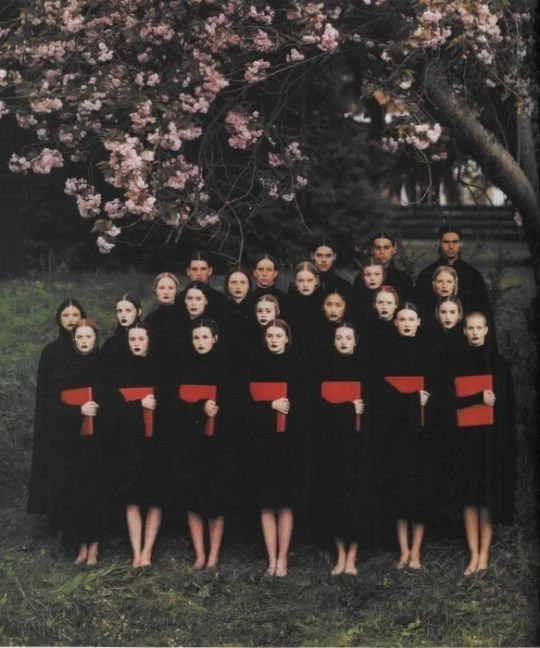

This is where unity turns coercive. Uniforms have long been used to erase differences under the guise of harmony. In Maoist China, the Mao suit flattened social distinction into a single silhouette, rendering individuality suspect and deviation legible as dissent. In totalitarian regimes, that same logic is formalized: sameness is drafted as control. The uniform normalizes compliance less through force than through repetition, training the body to associate similarity with safety and difference with risk. Over time, obedience can settle into a habit; the absence of decision can start to feel like peace. Social psychologists call this normative conformity, the impulse to align for approval or to avoid rejection.

Tenderness exists here too, not despite the uniform but because of it, in the small, sacrosanct comforts of repetition. Nani’s sarees have always made the world feel more traversable, as if her familiar silhouette were providence, proof that the day would hold. The same saree draped with deft fidelity, bangles soft against skin, a faint sillage of soap and chai following her through the rooms. My leotard does the same in a different key. I pull it on before ballet, and my spine finds its axis; I feel less scattered, less spectral. The ache in my hips feels purposeful again, my limbs remembering their old grammar, plié and tendu, as if the body never truly forgets. The redolent uniform becomes a grounding ritual, mollifying uncertainty by shrinking the vastness of this world within the peripheries of fabrics and figures.

Uniforms Through Time: A Brief History

The Renaissance Uniform

In medieval and early modern Europe, dress was not merely a matter of taste but statute: governments legislated who could wear silk, velvet, fur, and certain dyes, ensuring power stayed visually exclusive. Even color could be territorial: Tyrian purple, wrung from sea snails and rationed into privilege, proof that authority survives by becoming recognizable.

Renaissance finery then took that logic and made it sumptuous. Their perogatives prevented commoners from dressing “above their rank,” ensuring wealth and status stayed visually exclusive to nobility. Men’s doublets were padded and lavishly ornamented: Henry VIII once donned one embroidered with pearls and emeralds. For women, the corset became an instrument of both beauty and submission: Catherine de’ Medici famously banned “thick waists” at the French court, helping popularize the whalebone-stiffened bodice that cinched and elongated the female torso. These corsets, architectural marvels of wood and bone, sculpted a conical silhouette and ‘kept a lady in her place’ – a sartorial girdle on both body and agency. In effect, Renaissance finery was a uniform of hierarchy: jeweled brocades and tight-laced forms broadcasting a message of sanctioned order, each garment an exercise in control.

Modern fashion still pillages this opulent past. Designers mine the Renaissance for its drama and symbolism, translating courtly excess into contemporary statements. Alexander McQueen’s Fall 2013 collection was fit for a royal, with all white Elizabethan gowns showcasing ruff collars and pearls; waists cinched, and hips exaggerated in almost ecclesiastical grandeur. Only McQueen would put models in pearl-encrusted face cages and Tudor ruffs and make it look divine. Valentino’s couture show in 2016 went full Shakespeare, resurrecting the neck ruffle favored by 16th-century monarchs and pairing it with transparent embroidered gowns. Even Chanel has indulged in Renaissance revival: in 2013, Karl Lagerfeld sent out doublets and corseted looks adorned with feathers in place of farthingales, blending masculine and feminine in a nod to the era’s sartorial theatrics. Brocade and Corsetry signify painstaking craft and the stiff posture of privilege. When a modern woman slips into a Vivienne Westwood corset or a Dolce & Gabbana gold-brocade jacket, she’s not just wearing a garment; she’s cloaking herself in the echo of a power uniform that has survived, chameleon-like, across centuries.

The Old English Uniform

Fast-forward to the Anglo world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and you find another kind of uniformity: the crisp delineation of class through tailoring. In Regency and Victorian Britain, the tailcoat was king. Once a daring new cut for Georgian dandies, by the 1800s, the tailcoat had cemented itself as the formal costume of gentlemen. To wear a tailcoat in its heyday was to assert one’s place in the social order. For the middle classes, aping that look was taboo. Thus, the tailcoat itself became a gatekeeper; accompanying it, the “old school tie” has become shorthand for clannish alumni networks and upper-crust privilege. For generations, Britons established tribal loyalties through stripes and crests, whether on a student’s blazer or an army officer’s sleeve. In Edwardian times, even city bankers had their own strict dress codes (morning coats, top hats) that differentiated them from the masses.

Modern designers like Thom Browne refine it in shrunken suits that satirize schoolboy proportions; brands like Ralph Lauren sell us the fantasy of the Oxbridge blazer and cricket sweater as an aspirational lifestyle. Even the “school uniform” look has been in punk and subcultures. Even now, certain London dining clubs keep tailcoats and school ties like sartorial fossils of an era when what you wore announced who you were.

The Military Blueprint

Militaries pioneered the very idea of standardized dress to turn individuals into units – a visual conformity that said these legions serve a purpose beyond themselves. Over time, that blueprint spilled outward into civilian life: policemen, postal workers, pilots, nurses, hotel concierges, even schoolchildren lined up in neat rows of matching attire. There is a certain dignity about a uniform that commands respect. High fashion, ever the magpie for symbolism, has consistently commandeered military tropes to add edge and gravitas to civilian clothes. The trench coat is the classic example. Thomas Burberry designed it as trench gear in World War I – waterproof, strapped, with shoulder epaulettes for officers to display rank. Hollywood immortalized the style on Bogart’s slouched shoulders in Casablanca. Thus, a garment born of war became a cinematic symbol of weary, romantic heroism.

The brass-buttoned peacoat, once naval issue, now engenders a line of civilian chic. Even epaulettes and braided frogging have kept their lineage: from Hussar uniforms to Michael Jackson’s stage jackets, and later, Balmain’s inspiration for runway militaria. Yves Saint Laurent scandalized and delighted in 1966 with Le Smoking, essentially putting a woman in a man’s evening uniform, not completely military, but certainly a play on gendered authority coding. In recent years, brands like Burberry have reinvented the officer’s jacket or the camo print on city streets, because nothing telegraphs a certain swagger like militaria. The paradox is: garments once meant to enforce conformity have been widely adopted as expressions of individual style and rebellion. A punk in a surplus army jacket and a CEO in a custom-made naval peacoat are both, in their own ways, appropriating the same grammar. Such is the enduring spell of the military uniform.

The 1980s Uniform

No decade embraced the literal idea of fashion as armor more than the 1980s. In the era of Power Dressing, clothing was weaponized for the boardroom. The typical silhouette was the now-iconic power suit: big-shouldered, sharply tailored, unapologetically aggressive in its polish. Designers like Giorgio Armani led the way with suits that softened the menswear cut just enough to flatter, but kept the broad shoulders and clean lines to display dominance. Thierry Mugler and Claude Montana further exaggerated the shoulder pads into something almost futuristic, where women in their suits looked like stylish linebackers.

Julia Roberts in a power suit. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

Margaret Thatcher. Image courtesy of Selwyn Tait/ Selwyn Tait/CORBIS SYGMA.

In an era of Working Girl and Margaret Thatcher, it was announced that femininity and authority were not mutually exclusive. Thatcher herself became an unwitting style icon: the “Iron Lady” in her tailored suits, making the point that a woman could lead the free world without donning a man’s uniform, but by reinventing her own. The power suit phenomenon also permeated pop culture. Television dramas like Dynasty gave us Joan Collins as Alexis Carrington, swanning about in jewel-toned suits with punitive shoulder pads and nipped waists, every outfit a gauntlet thrown. The 1980s taught us to see fabric as a nod to confidence.

The Meta/Superhero Uniform

Not all uniforms are inherited from history; some are conjured from the imagination. The superhero is a modern myth whose costume functions as a moral insignia. These uniforms are a mythological costume communicating a hero’s identity and code: The cape becomes a kinetic halo, the mask is anonymity with purpose, the skin-tight bodysuit renders a physique archetypal with exaggerated ideals, and the chest emblem propounds a public oath. Designers from Thierry Mugler to Jean Paul Gaultier have drawn directly from the superhero playbook, sending models down runways in looks that could clothe the Avengers. Mugler in the early ’90s showed metallic bustiers and winged shoulders that turned women into glamazonian cyborgs. These looks coincided with a cultural fascination for comics and sci-fi; fashion was picking up on the idea that a costume could confer an extraordinary persona.

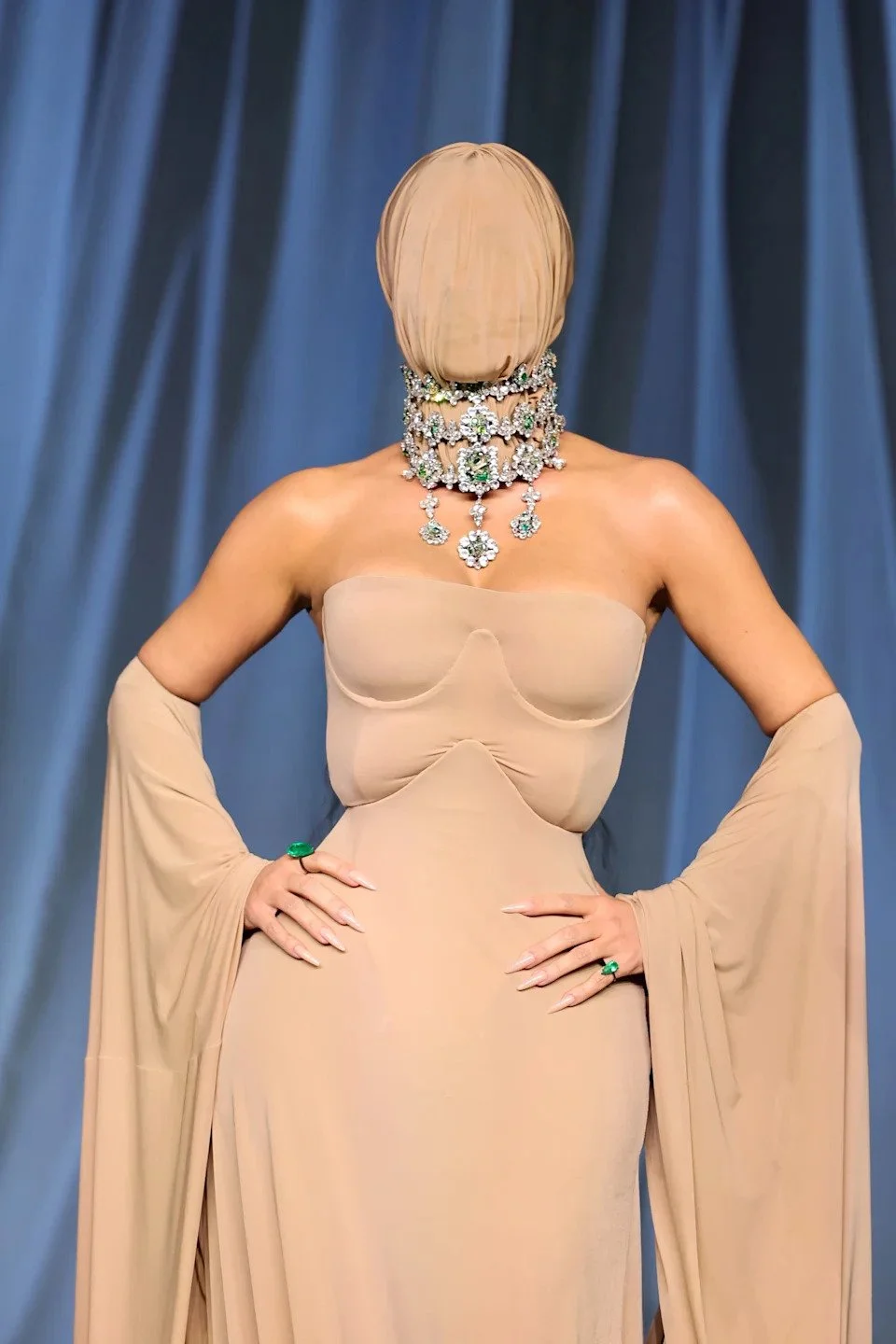

One fascinating aspect of the superhero uniform is the use of anonymity as power. The mask is a crucial component: by hiding the person, it turns the wearer into a symbol. Behind Batman’s cowl or Spider-Man’s full-face mask, the individual is subsumed by the idea they represent of justice, vengeance, and hope. Fashion has flirted with this kind of facelessness. Martin Margiela, for example, notoriously had his models wear full-face coverings and bejeweled masks in runway shows, deliberately erasing individual identity to let the clothes speak. This is a superhero statement of ethos: it’s not about me; it’s about the mission (or the design). In a similar vein, labels like Balenciaga under Demna Gvasalia have toyed with masks and morphsuits, suggesting that in our hyper-visible age, the ultimate power move might be to make oneself an enigma, an icon without a face.

The superhero uniform appeals because it is stark and bold: here stands a hero, or a villain, in full technicolor. And in borrowing those cues, fashion lets us playact some of that moral theater in our own lives.

The Cultural Uniform

Across the world, certain garments transcend mere fashion to become repositories of culture, identity, and collective memory. A saree, for instance, is not just six yards of fabric, but a motif of a woman’s region, religion, and stage of life. A kimono in Japan encodes formality and season in its patterns and layers, with every motif carrying meaning. A Palestinian keffiyeh scarf, woven in black-and-white checks, stands unmistakably as a symbol of resistance and solidarity, laden with political history. These are what we might call cultural uniforms: traditional attires that both express personal identity and immediately situate the wearer within a larger social narrative. They have the weight of generations behind them with a lineage in every fold. For many, wearing such garments is a daily act of connection to heritage, and for diasporic communities, putting on a cultural garment can feel like donning the armor of identity in a foreign land.

Cultural exchange in fashion can be beautiful and respectful. There are designers, often from within those cultures or in genuine collaboration, who bring traditional elements into contemporary fashion in a way that honors their origin. British-Jamaican designer Grace Wales Bonner, for example, infuses European heritage with an Afro-Atlantic spirit in her collections. Her work is informed by deep research, and she often works with Black artisans or incorporates historically significant motifs, effectively celebrating cultural uniform elements rather than just exploiting their exotic appeal. Indian designer Dhruv Kapoor might take inspiration from indigenous textiles or the silhouette of a sherwani. We’ve seen brands like BODE in New York repurpose antique textiles (quilts, Kantha embroideries from India, etc.) into one-of-a-kind garments that carry their stories visibly. When done right, it feels less like appropriation and more like a new chapter for a cultural uniform in a globalized context.

The Luxury Uniform

Luxury has its own etiquette of visibility: it does not need to announce wealth, only to be recognized. The luxury uniform is not excessive, but with composure. This is the true choreography of luxury: the same codes, rehearsed with such class that they pass as instinct.

The modern luxury uniform begins, in many ways, with Chanel: not simply because of the logo, but because Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel re-scripted what elegance could do. She borrowed from the practical world, from menswear and maritime ease, and made it feminine without making it fragile. The Breton stripe, once literal sailor utility, became Riviera polish in her hands. By the 1950s, the silhouette had fashionably crystallized the collarless tweed suit, braid and gilt buttons, a straight skirt that draped its wearer in utter opulence and elegance. This is why a Chanel suit could become political shorthand on Jackie Kennedy and still feel culturally legible decades later. From there, the luxury uniform branches into accessories that function like a pedigree in miniature. Van Cleef & Arpels’ Alhambra clover, introduced in the late 1960s, is luck made conspicuous in the quietest way: a motif repeatedly adorned on dainty collarbones until it becomes unmistakable. Cartier’s Love bracelet turns intimacy into hardware, a bangle worn so continuously it begins to look permanent, like the wrist has been claimed by a certain kind of life. Hermès perfects the slow theater of scarcity: the Birkin and Kelly as objects that don’t just carry belongings, but carry time and inheritance. And then the everyday choreography of it all: a Bottega cassette tucked under an elbow like an afterthought, sunglasses pushed into the hair with practiced indifference, a Hermès scarf that makes the neck look instructed, gold hoops that never come off, a watch that reads like lineage. Even the smallest gestures become part of the uniform.

“Darling, if you fall, fall in Dior” is the sacrosanct belief that life, in all its capriciousness, ought to be met with that composure so disciplined it looks innate. Luxury is not merely what you procure; it is the tutelage of the self into a certain bearing, an almost regal refusal to be seen as floundering. Luxury becomes a paradigm of conduct with the virtuosity of seeming unperturbed while everything else totters. It is the principle that chaos is allowed, but only in good tailoring.

The Futurist Uniform

For over a century, fashion designers (and filmmakers, writers, dreamers of all stripes) have been sketching out a form of a futuristic uniform. A few key motifs are the bodysuit or jumpsuit with high-tech functionality, metallics and shiny materials, and designs generated or optimized by 3D printing or technology. The futurist uniform is often imagined as egalitarian. The space-age look first took hold in the 1960s, when designers like André Courrèges and Paco Rabanne broke with the past with shiny retro designs for a better tomorrow. Courrèges gave us angular mini-dresses, go-go boots, and helmets that looked apt for a moon base. Rabanne created dresses out of metal discs and plates linked like armor. They established a visual lexicon that uniforms of the future in popular imagination would draw from: reflective surfaces, unconventional materials, and an almost cartoonish simplicity of shape.

Image courtesy of Vogue.

As the decades rolled on, futurist fashion dreams often mirrored current technological fascinations. Iris van Herpen, a couturier of our current times, uses 3D printing, laser-cutting, and chemist-like fabric alchemy to create outfits that truly look not of this world. Her dresses might feature sci-fi exoskeleton elements or liquid-looking patterns that shift as the model moves. This hints at a future uniform of infinite customization with each person’s bodysuit woven on demand by AI to perfectly fit and support their body, adjusting temperature, monitoring health, maybe even changing color or shape based on mood or social setting.

Meanwhile, techwear in street fashion suggests the utilitarian and militaristic futurist uniform for city dwellers. Brands like Acronym and tech-leaning lines from Nike or Y-3 envision people dressed in water-resistant, pocket-laden, breathable fabrics in shades of black and grey. These clothes often incorporate hidden hoods, transformable pieces, and materials like Gore-Tex and Kevlar blends. Utopian designs emphasize cleanliness, unity, rational design; dystopian ones emphasize protection, anonymity, survival. In both, we see an impulse to simplify and codify dress for a high-tech world.

And so the uniform keeps moving, century to century, like a pattern that refuses to die. It leaves the court and reappears in a classroom. It migrates from the trench to the runway, from the boardroom to the screen, from inherited cloth to algorithmic sheen. Somewhere in that long relay, we are still doing the same human thing: arranging ourselves into a paradigm. ….And maybe that is the quiet truth beneath every uniform: history may draft the silhouette, but we are the ones who decide how it lives on us.