The NIL Effect: How College Athletes Redefine Fashion and Fame

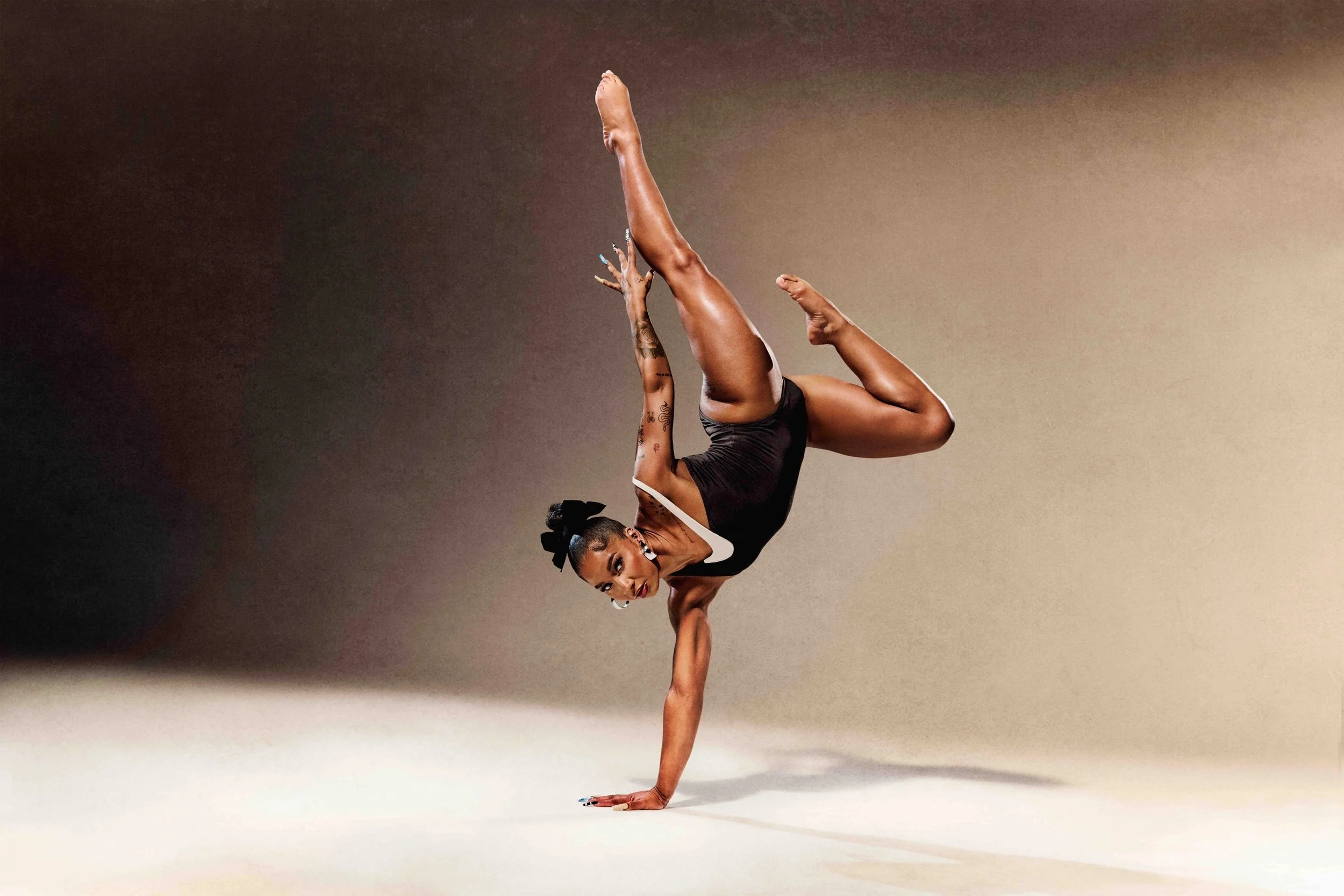

Jordan Chiles for Nike.

NIL stands for “Name, Image, and Likeness”, and refers to the legal right for college athletes to make a profit from their own image and personal brand.

Despite their widespread popularity, college athletes have been prohibited from earning money for participating in sports. Since its formation in 1906, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has barred athletes from profiting off any paid sponsorships, endorsements, or social media campaigns. The idea behind keeping NIL money out of college sports would, in theory, preserve the purity of athletics, prioritizing education over college sports. Students are students first and athletes second. The NCAA claimed restrictions would also reduce the unfair advantage that wealthier schools have, alleviating the concern that athletes would choose to attend schools that would offer them the most money in potential partnerships.

However, collegiate sports are a multi-billion dollar sector, earning roughly $13.6 billion in revenue in 2022, which is more than what the Major League Baseball, the National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League earn individually. With earnings this lucrative, the NCAA had a clear financial incentive to control NIL rights, wanting “to maintain control over revenue-generating opportunities, including broadcasting rights, merchandising, and sponsorship deals relating to athletes’ participation.” (EPGD Business Law)

However, the NCAA’s air-tight control on NIL ended in July 2021, with the landmark decision to permit college athletes own and profit from their NIL. This ruling stood on the shoulders of decades-long legal action and widespread public support for change in NIL law. Today, NIL law is not federally regulated, but is up to the discretion of individual states and schools.

Arch Manning for Warby Parker.

Student athletes can make money from NIL through sponsorships, social media campaigns, autograph signings, and public appearances. Arch Manning, the quarterback for the Texas Longhorns, currently has the highest NIL deal in history, valued at approximately $6.8 million. This eye-popping number includes deals with Warby Parker, Uber, Vuori, and EA Sports. Livvy Dunne, a former LSU gymnast and the most followed college athlete on social media, is valued at over 4 million. She has deals with Crocs, Vuori, and Sports Illustrated.

Here at UCLA, women’s basketball player Sienna Betts recently signed a deal with New Balance. Gymnast Jordan Chiles, leveraging her social media presence and Olympic fame, returned to UCLA with deals with Nike, Urban Outfitters, and Toyota.

But what do these lucrative deals mean for culture and society at large? NIL has outspoken supporters and vociferous critics. I argue that this divisiveness falls upon three axes:

LIBERATION AND EMPOWERMENT

Many NIL supporters acclaim the deal to be one of empowerment and self-ownership. The right to wield your image as your own, to carve out the financial gains that you deserve to have. Someone is profiting from partnerships and pocketing money, and if it's not athletes, it's the universities and the NCAA. It seems fitting that college athletes get a chunk of this transaction, considering they are the reason the public buys game tickets and tunes into college sports on TV. Moreover, intellectual property rights are increasingly pertinent in the digital age. An athlete’s face is already plastered all over college campuses and social media, so it naturally follows that they should have a say in where and how their likeness shows up. As for the issue with AI, many are worried that their image and intellectual property will be fed to AI models without their knowledge or consent–and then regurgitated by algorithms to the public. Notably, in a high-profile case, the New York Times has sued OpenAI and Perplexity for copyright concerns that fall under this umbrella.

The NIL fits seamlessly into the increasingly hyper-individualistic attitude that dominates Western thought. In a culture that prizes personal branding and self-determination, NIL simply formalizes the expectation that every person should maximize their own market value. It reinforces the idea that one’s image is a personal asset to be cultivated and monetized. It’s an extension of the broader societal shift toward treating the self as a standalone economic unit.

SELF-EXPRESSION

Perhaps NIL is as simple as self-expression. Wearing certain brands or styles works as a form of signaling– signalling what group we belong to, what values we have, where we fall on the socioeconomic ladder. Wearing what our favorite college athletes are wearing symbolizes our idolization and support for them.

Clothing brands, along with tech, lead the collegiate NIL market, which exceeds $15 million in spending across major categories. Both Arch Manning and Livvy Dunne, two of the highest-paid college athletes, have signed major deals with popular athleisure brand Vuori. Even luxury brands have thrown themselves into the fray. Miami football quarterback Cam Ward has teamed up with Giorgio Armani, Texas track athlete Sam Hurley joined Ralph Lauren, and UNC’s basketball player Deja Kelly is the first college athlete to sign a deal with Tommy Hilfiger.

Essentially, we just want to dress and look like the people we want to be. A bulk of NIL deals are with fashion companies, which makes sense: clothing is one of the most visible and immediate ways people construct identity. Nike’s Air Jordan tennis shoes are the prime example of the synergy between fashion and sports, and a high that all clothing companies still chase, decades later. The Air Jordan was introduced through rookie basketball player Michael Jordan in 1985, who would get fined for wearing them every time he played because they broke NBA uniform standards. Nike used the controversy as the backbone of their marketing campaign, and along with Jordan’s obvious talent, created a fashion moment that permanently imprinted itself into culture. You too, could be Michael Jordan, leaping impossibly high across the court–if you wore a pair of Air Jordans.

A DEEPENING SPIRAL INTO CONSUMERISM?

However, NIL has darker undertones than simple empowerment or self-expression. In our consumerist society, to own is to belong. On TikTok and Instagram, you might be familiar with “clothing-hauls”, “kitchen restock” or “beauty-routine” videos. Perfectly austere pantries with goods in identical containers, all labelled. Mini-fridges stocked full with the newest, anti-aging Korean skincare. A closet full of Zara’s newest items. You’ve seen her on your feed– a young woman makes herself an iced strawberry matcha in the morning, goes to a pilates class with a yoga mat and matching workout set, then buys some new makeup, goes grocery shopping to make herself a healthy dinner, and applies her ten-step skincare routine before bed. Everything is linked in my bio! she writes in the comments.

Livvy Dunne for Vuori.

Who would we be without our stuff? Identity in the twenty-first century seems to be rooted in what one owns. Fans no longer just admire athletes—they are invited to purchase a version of their identity. This reinforces the idea that selfhood and social belonging are inseparable from consumption. And since college sports have viewership numbers in the tens of millions, it’s only natural that NIL fashions athletes as micro-influencers. It could be argued that influencer culture doesn’t affect gameplay directly and just revolves around the world of sport. But nothing exists in a vacuum, and with the new athlete/influencer dynamic at play, everything becomes a potential marketing opportunity. Authenticity is performed, and branding is constant.

NIL has its place on our campus, too. Currently, 441 UCLA athletes are available to sign NIL deals, according to the Westwood Exchange, “a student-athlete NIL business registry”. That’s more than half of the student-athlete population. Additionally, you can access the NIL Store, and buy officially licensed NIL merchandise, like t-shirts and jerseys, with your favorite UCLA athletes’ names emblazoned upon them.

NIL at UCLA and other colleges is still an ongoing battle– it looked different a few years ago, and will likely look different a few years from now. Many describe the current times as the “wild west” of NIL. Deals are evolving, athletes’ personal brands are growing, and new industries are constantly entering the mix. NIL at UCLA is a reflection of broader cultural trends, a microcosm of self-expression, identity, and consumerism all wrapped together. Whether you agree with it or not, NIL has forever changed the playing field for collegiate athletics. Money for play is not left to the professionals, but to the student athlete who sits in front of you in your History class. And every athlete has a brand worth playing for.