The Ethics of Getting More Chinese

Techno-Orientalism in Fashion and Media

Still from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) Source: Liminal Mag

Our sci-fi, carbon-steel apocalypse is closing in. In 2025, artificial intelligence begins to overtake our jobs and our lives. Glossy dark-haired androids in factory lines will replace all minimum wage labor by 2027, and in 2030 we can finally replace all human connection with silicone robots and GenAI holograms that look uncannily like… Japanese schoolgirls. The imagery of a speculative future, rampant with anxieties around advancing technology, is caught in an unknowable space trapped between Dystopia and Utopia– but why does it always seem ambiguously Asian?

DISCUSSING ORIENTALISM

To understand our Western perceptions of East Asia at large is to understand Orientalism. Orientalism, popularized by Edward Said, is the Western representation and portrayal of the East - or the “Orient”, as a romanticized and exoticized Other – both primitive and barbaric. Evident in how these societies are often portrayed, Orientalist artwork often sensationalizes and dehumanizes the East, placing their perceived exoticness and primitivity in contrast to supposed Western enlightenment – serving as justification for Western colonial dominance and superiority.

La Japonaise (1876) by Claude Monet. Source: Wikipedia

Orientalism’s undercurrents are far-reaching in the history of racist attitudes toward Asia at large. Examples include the Yellow Peril, or the western fears of Asian people as an ambiguous and organized threat, fuelled by xenophobia historically in examples like the Chinese Exclusion Act– seeping into policy and society at many levels.

Orientalism has always been deeply intertwined with fashion, art, and textile history. The Western world has always looked to East Asia for aesthetic inspiration, evidenced by historical trends of Chinoiserie – faux “Chinese” products catered to the broader European market. In fact, art movements such as Impressionism– lauded as one of the first markers of Modern Art in the Western canon– are inspired by the Ukiyo-e block prints of Japan. It’s a continued pattern of the “West” appropriating, taking from other parts of the world–in this case, East Asia. Appropriation garners praise when reframing Asian art in a Western aesthetic lens, shifting perceptions of these art forms to “exotic” and “subversive”, while maintaining East Asia in a position of inferiority. While this appropriation may initially come from a place of appreciation, an issue of fetishization and othering emerges when aesthetic culture is stripped away from societies and identities, and becomes a stereotypical caricature– while the people whom the culture belongs to receive no credit.

THE BIRTH OF THE TECHNO-ORIENT

But long gone are the old stereotypes of the Orient, which we now understand as overtly offensive and stereotypical. East Asia, primarily Japan, Korea, and China, has undergone rapid modernization over the past 30 years. Their technology and industry are overtaking those of the Western world as East Asia vies for America's position as the socioeconomic center of the World. The image of an ancient, age-old Asian culture is at odds with its towering skylines and high-speed technology— a dissonance that the “West”, which prides itself as the most “developed” in the world, has trouble coming to terms with.

Exemplifying this dissonance, Techno-Orientalism refers to the phenomenon of imagining Asia or Asians in hyper-technological terms, as both technologically advanced and intellectually primitive. Popularized by David S. Roh, Betsy Huang and Greta A. Niu, the term was introduced mainly in the context of speculative fiction and media, focusing on literary genres such as cyberpunk. Yet, outside of academia and media studies, the consequences of Techno-Orientalism are far-reaching in our today’s digital autocracy. A continuation of ideas such as the Yellow Peril, Techno-Orientalism is a continued othering and cultural depersonalization of the East through associations with technology and robotic forms. The fear of the East as a sinister agent is tied to its technological prowess, thus depicting Asian people as a non-human – perhaps subhuman – other, machine-like and robotic, marking a global dystopia as intrinsically Asian in appearance.

When focusing specifically on East Asia, larger cultural waves fit into this framework. Recent Sinophobia has its roots in Techno-Orientalism, with the Chinese government’s relationship to the US always contentious. Prominent examples range from consistent fearmongering of the CCP meddling in American affairs via advanced TikTok spyware technology, to frenzy over COVID-19 leading to rampant xenophobia directed toward Asian-Americans, as well as recent news headlines of deportations and prosecutions of Chinese scientists weaponized as political fodder for US-Chinese relations. These headlines paint East Asia at large as an organized threat, and its populace as non-human pieces of an active danger to Western society, weaponizing Techno-Orientalist fears to further political divides.

TECHNO-ORIENTALISM IN LABOR

In laying the groundwork for Orientalism and Techno-Orientalism, Roh, Huang, and Niu recount: In 1881, California Senator John Miller described Chinese immigrant workers on American railroads as “machine-like . . . of obtuse nerve, but little affected by heat or cold, wiry, sinewy, with muscles of iron; they are automatic engines of flesh and blood; they are patient, stolid, unemotional . . . [and] herd together like beasts” (qtd. in Chang 130).

The dehumanization of the Asian laborer continues in the Western view of production, especially in fast fashion. When we think of clothing manufacturing, it's easy to imagine rows and rows of masked Asian migrant laborers in run-down corporate factory towns, stoic and mechanized— a direct parallel to John Miller’s quote. These photos have made their way into mainstream reporting, tying the visual language of overconsumption and hyperproduction to East Asia and the Asian body. As Roh, Huang, and Niu put it, this flawed concept constructs Asians “as mere simulacra and [maintains] a prevailing sense of the inhumanity of Asian Labor - the very antithesis of Western liberal humanism”. While the horrors of overproduction are real, the visuals and rhetoric of East Asian manufacturing as relentless and machine-like are Techno-Orientalist conceptions illustrated in Western media.

Western coverage of Asian textile factories. Source: Reuters.

The image of machinic hyperproduction as inherent to Asian production has cemented the phrase “Made in China” as ubiquitous with cheaply made, low-quality goods. Yet as unethical practices in garment sweatshops and low-quality clothes – issues of overproduction at large – still persist in manufacturing on American soil, much of the stigma is deeply hypocritical – an effect of Techno-orientalist conceptions of the Asian body.

TECHNO-ORIENTALISM IN FASHION AND MEDIA

Inadvertently, East Asia has become coded as Mechanical. Aspects of the uncanny and robotic, contradictions between the synthetic and the mechanical, the primitive and underdeveloped, are at the core of techno-orientalism as it relates to fashion: not only as a source of labor, but also an object of fetish.

Of course, the association of East Asia with futurity stems from seminal works of Asian sci-fi media–Japanese films like the cult classic Tetsuo: Iron Man (1989) popularized the genre of body horror, pioneering the concept of the Cyborg–part machine, part human. Ghost in the Shell’s (1995) sleek robots and Akira's (1988) futuristic red leather jackets are large influences on pop culture, inspiring streetwear brands and trends, and are celebrated worldwide.

Yohji Yamamoto's collaboration with Ghost In the Shell. Source: Yohji Yamamoto

Kanye West referencing Akira (1988). Source: LA Times, IMDB

MSCHF boots referencing Osamu Tezuka’s Astroboy. Source: WWD, GoodReads

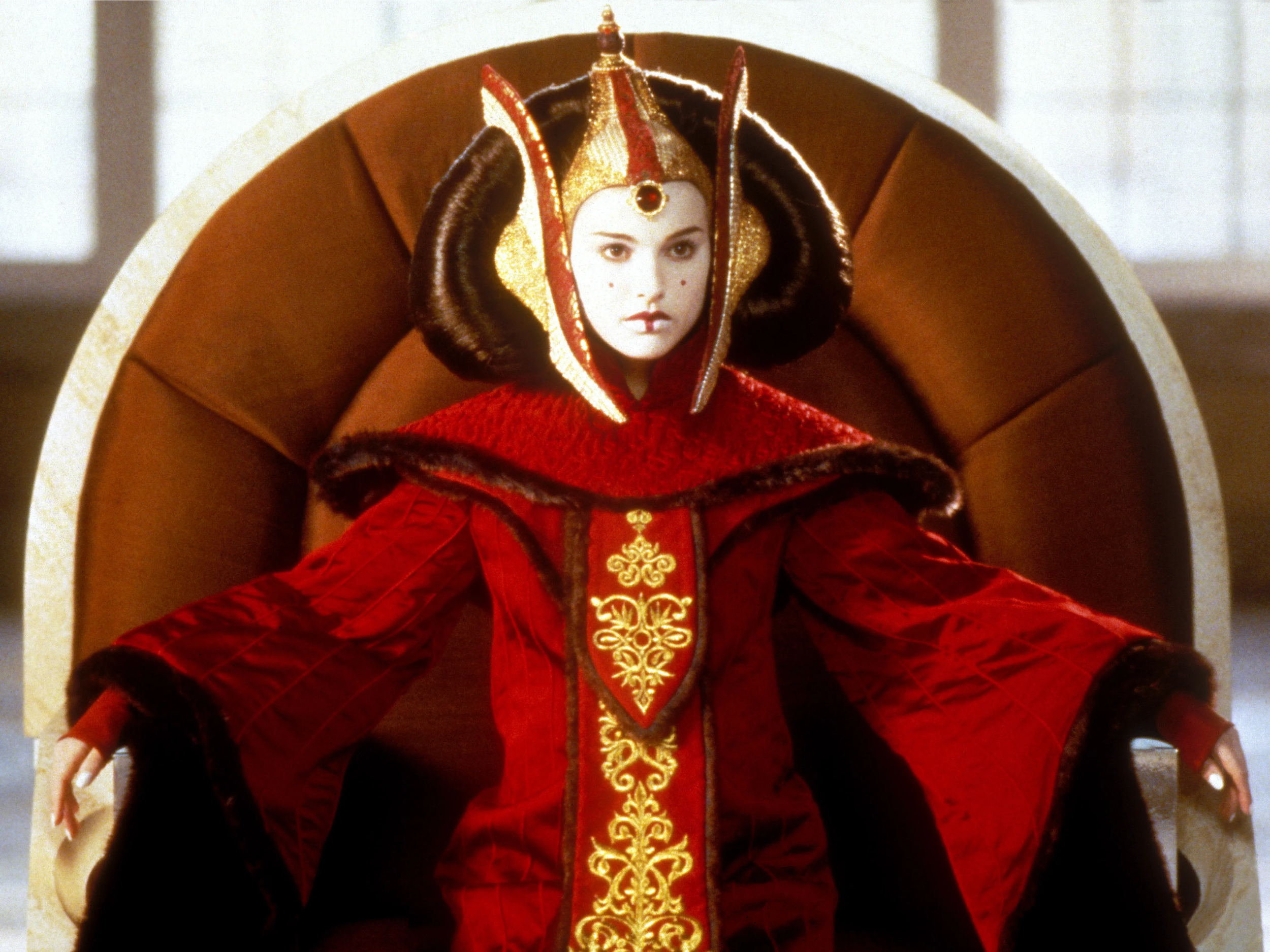

These kinds of cultural exchanges aren’t inherently negative– but often, the lines between appreciation and appropriations of techno-orientalism become blurred. John Galliano, upon returning from a three-week trip to China and Japan, created an ambiguously “Asian inspired” 2003 collection: white models were painted in cyborg mask-like Geisha-inspired makeup, and dressed in vaguely cheongsam and kimono-inspired silhouettes, displayed along with Chinese dancers and circus performers– an exoticized amalgam of Eastern inspirations. In Raf Simons SS 2018, models walk down a fluorescent runway, carrying paper lanterns and signs with kanji as props in homage to Techno-orientalist cyberpunk fantasies such as Blade Runner. Techno-Orientalism is also extremely prevalent in film and movie costuming in scifi: iconic characters such as Queen Amidala from Star Wars, take inspiration from Mongolian tribal attire – pulling from underrepresented cultures as a source of inspiration to evoke futurity and exoticism.

Raf Simons SS 2018. Source: SHOWstudio | John Galliano for Dior, SS 2003. Source: The Independent | Padme Amidala in Star Wars. Source: Wired | Woman in traditional Mongolian attire. Source: Wikipedia

While they may come from a place of appreciation, these aspects have become far removed from the cultures they are associated with, and these inspirations become stereotypical simulacra, conflated with a dystopian, technological future, and touted as subversive and “contemporary” in the mainstream when parroted by Western designers and artists. Asian fashion and aesthetics are thus exaggerated to project an image of the speculative future–taking the shape of "primitive" East Asian cultures but without the actual people.

Milan’s Gentle Monster store. Source: PauseMag

Another case study of potential techno-orientalism is the Korean eyewear brand Gentle Monster. Known for their strong branding, their marketing and products feature a sleek, silvery, futuristic, almost cyborg aesthetic– its in-person locations featuring larger-than-life, Instagrammable disembodied robot parts. Gentle Monster has also wholeheartedly adopted AI, with its most recent campaign featuring Tilda Swinton amongst a crowd of computer-generated figures, complementing Google’s $100 million investment in the brand’s development of AR/AI smart glasses.

` Gentle Monster’s unique branding differentiates it drastically from other eyewear brands, allowing the brand to proliferate into the American mainstream– spotted on the likes of celebrities such as Rihanna and Lady Gaga. Gentle Monster’s image may not be overtly harmful– but as it plays on techno-orientalist aesthetic choices, it’s worth questioning the implications of the brand’s popularity as it expands beyond an East Asian market.

Gentle Monster’s 2024 campaign. Source: The Impression

Within online fashion trends and tropes, the now infamous archetype of the Performative Man has been the center of much discourse–the often non-Asian selvedge denim clad, Tabi wearing, Labubu strapped individual with a matcha latte in hand, who collects archive Yohji and If6Was9 on Grailed and uses words like Wabi-sabi, Feng Shui, and jokes about “becoming more Chinese”. Many traits of the trope are a simulacra of Asian culture, now associated more with the Digital than their cultural traditions and influences. The Performative Man’s appropriations are markers of Screen Time, symbols of curated consumption and being “in the (digital) know”. A trickle-down effect from the broader strokes of Techno-Orientalism, aspects of Asian culture are boiled down and lauded as hollow markers of Internet-laced cultural capital, through a fetishistic lens that conflates the Asian with the Hyper-technological.

Examples of the Performative Man (Source: @DodoFits on X, @itsbrianpark on TikTok)

Despite these examples, the aesthetic niche of East Asian culture and the Technological isn’t inherently unethical, and can be used to critique our Techno-Orientalist notions. Rapid industrialization and modernization is a subject of commentary for many contemporary East Asian artists– one of the most prominent being South Korean conceptual artist Nam June Paik, who juxtaposes Buddhism and the spiritual with modern-day technology. Chinese artist Cao Fei directly tackles the hyper-production and labor in Whose Utopia (2006), where she documents the factories in China’s Pearl River Delta region, highlighting the dreams and hopes of the workers. Displayed on an international scale, her choices humanize the workers that the world often overlooks, beyond their mechanized tasks.

When it comes to Techno-Orientalist imagery, there is an inherent difference between Western markets that exploit these images of the “East” for their own gain, and the artists often native to these countries who create fashion and media inspired by their experiences. From national governments to fashion companies, institutions at large often perpetuate hyper-technological images of East Asian countries, mechanical and devoid of humanity, with the effect of exoticizing and dehumanizing the populace. Onlookers and consumers should be wary of how these aesthetics are integrated into our lives, and our choices as consumers of fashion and imagery: How do we protest fast fashion, overproduction, and the exploitation of labor overseas, in a way that is wary of these tropes? And how do we determine whose culture we deem futuristic– and where do the people it belongs to exist in your speculative future?

While some may find positives in the representation and success of East Asian culture in the economic and social mainstream, it is a double-edged sword built on a fetishization and colonization of the East. Techno-orientalism serves as a reminder that long-standing structures such as Orientalism are systemic patterns that don’t just go away in the modern age–its sepia-tint and scrolls are merely traded out for fluorescent backdrops and metallic cyborg bodies. Innovation and new technology won’t always solve our problems, but can merely shift how they appear.